THE FOOTBALL LEAGUE

(The Football League championship trophy)

Formation of the Football League

A director of Aston Villa, William McGregor, was the first to set out to bring some order to a chaotic world where clubs arranged their own fixtures, along with various cup competitions.

(William McGregor)

On 2 March 1888, he wrote to the committee of his own club, Aston Villa, as well as to those of Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Preston North End, Stoke and West Bromwich Albion; suggesting the creation of a league competition that would provide a number of guaranteed fixtures for its member clubs each season. His idea may have been based upon a description of a proposal for an early American college football league, publicised in the English media in 1887 which stated: "measures would be taken to form a new football league ... [consisting of] a schedule containing two championship games between every two colleges composing the league".

The first meeting was held at Anderton's Hotel in London on 23 March 1888 on the eve of the FA Cup Final. The Football League was formally created and named in Manchester at a further meeting on 17 April at the Royal Hotel. The name "Association Football Union" was proposed by McGregor but this was felt too close to "Rugby Football Union". Instead, "The Football League" was proposed by Major William Sudell, representing Preston, and quickly agreed upon.

Although the Royal Hotel is long gone, the site is marked with a commemorative red plaque on The Royal Buildings in Market Street. The first season of the Football League began a few months later on 8 September with 12 member clubs from the Midlands and North of England: Accrington, Aston Villa, Blackburn Rovers, Bolton Wanderers, Burnley, Derby County, Everton, Notts County, Preston North End, Stoke (renamed Stoke City in 1926),West Bromwich Albion and Wolverhampton Wanderers.

These were comparatively primitive times, when players did not wear shirt numbers and stayed on the pitch at half-time; goalkeepers sported the same tops as outfield players; and two umpires officiated the game, referring only occasionally to a touchline referee. The introduction of the penalty kick was three years away, as were goal-nets to prevent the frequent disputes over whether the ball had passed between the posts.

The first season’s fixtures had been drawn up as late as 23rd July 1888. Another fact that will raise eyebrows today is that the League programme had been running for 11 weeks before the system of two points for a win and one for a draw was agreed upon (some of the 12 founding clubs had argued that points should be awarded only for a victory).

First things first

Years of debate over who scored the first ever goal in league football anywhere in the world when research at the British Library showed that Bolton Wanderers forward Kenny Davenport’s strike at approximately 3.47pm on Saturday 8th September, 1888 was the first ever goal in The Football League.

The match between Wolverhampton Wanderers and Aston Villa played the same day kicked off at 3.30pm rather than 3.00pm as previously thought by the game’s historians. Consequently, the own goal scored in that match by Aston Villa full-back Gershom Cox after 30 minutes would not have been the first ever goal.

(The old Pikes Lane stadium, where the first League goal was scored)

Kenny Davenport 1862-1908

Kenny Davenport was born in Bolton and played for Bolton Wanderers for nine seasons after joining the club from local rivals Gilnow Rangers in 1883. Two years later he became Bolton’s first ever England international when he played in a 1-1 draw against Wales at Blackburn.

As an ever-present in the first League season he also scored 11 goals. Normally an inside-left, Davenport made 56 League and twenty-one FA Cup appearances for Wanderers, scoring 36 goals. He left the club to play for Southport in 1892, just two years after he made his second appearance for his country, when he scored twice in a 9-1 victory against Ireland in Belfast in 1890.

Davenport died in 1908 aged 46.

(The first League goalscorer, Kenny Davenport)

What were the original rules?

At the beginning of the season it was decided that whichever team won the most games would be champions. A few weeks in this was deemed unfair as it made drawing no better than losing, so the League decided to award points: 2 for a win, 1 for a draw. In the end, this rule change made little difference; had it stayed in the "most wins" format, the only change would have been the move of Accrington to 10th and the elevation by one place of Everton, Burnley and Derby County.

Beginning with the season 1894–95, clubs finishing level on points were separated according to goal average (goals scored divided by goals conceded), or more properly put, goal ratio. In case one or more teams had the same goal difference, this system favoured those teams who had scored fewer goals. The goal average system was eventually scrapped beginning with the 1976–77 season.

During the first five seasons of the league, that is until the season 1893–94 re-election process concerned the clubs which finished in the bottom four of the league. One exception being in the 1889-90 season where Aston Villa and Bolton Wanderers finished level on 19 points and it was agreed the neither would face re-election.

So, what other League 'firsts' can be verified?

The first 10,000 attendance came for Everton’s 5-2 defeat of Accrington at Anfield – yes, Anfield, their original home before relocating to Goodison Park - where there was another late kick-off due to the tardiness of the visiting team.

Accrington’s John Horne suffered a cracked rib and became the first goalkeeper replaced by a team-mate (substitutes were not sanctioned until 1965).

A week later came The Football League’s first 10-goal thriller, if you will – a 5-5 draw between Blackburn and Accrington -- and Rovers’ first scorer, Jack Southworth, went on to play violin in the Halle Orchestra.

The first player cautioned was a Scot, Alec Dick, of Everton, “for striking a Notts County player and using foul language”, offences for which he publicly apologised.

In the early years of association football, hacking was still a widespread means of dispossessing an opponent. Perhaps with that in mind, William McGregor said proudly in 1891 that “not a single fatal accident” had been recorded.

The first transfer between League clubs had not been long in coming either, Preston’s Archie Goodall switching to Aston Villa in October 1888. Although no fee changed hands, McGregor, who was also a Villa director, made it clear he opposed such deals.

The Father of the League would have been even less impressed, one suspects, by the 'market' in players that swiftly developed. When Dan Doyle left for Celtic in 1892 it was reported that Everton sought to lure him back with wages of £5 per week - and the tenancy of a pub.

Villa were the League’s first runners-up, Stoke the first wooden spoonists although they were re-elected at the annual meeting in 1889. Of the new applicants, Newton Heath, who became Manchester United, received a solitary vote.

Stoke’s reprieve was short-lived. At the end of the second season they lost their place and joined the Football Alliance, formed by clubs aspiring to League status. In came Sunderland, signalling the end of the even split between six Midland clubs and six from Lancashire.

Expansion

The League's expansion continued into Yorkshire in 1892, when it was agreed to have a 16-club First Division and a 12-strong Second Division. Sheffield Wednesday, representing the city renowned as 'the cradle of football', were voted in with Nottingham Forest, and Newton Heath.

The south remained virgin territory for the League for another year. Woolwich Arsenal, from south-east London, then became members, as did Newcastle United and Liverpool (who replaced Bootle, thereby ending the first fierce Merseyside rivalry, between Bootle and Everton, and launching another).

Modern problems

Newcastle’s first game was away to Arsenal, the sort of pairing which would set 21st-century observers quipping about the mischievousness of the fixture computer. After travelling by overnight train and going sight-seeing in the capital, some players were said to be asleep when they arrived at the ground in Plumstead. They drew 2-2 before the long haul back to the north-east.

With the two-tier League came Test matches, a kind of Victorian play-off system to decide promotion and relegation. At the end of 1892/93, Newton Heath stayed up by beating Small Heath (later Birmingham City) in one such game.

However, the Tests were discredited in 1898. Stoke and Burnley -- both knowing a draw would ensure survival for one and promotion for the other -- acted out a mutually convenient barren stalemate without a single shot on goal. Automatic promotion and relegation was promptly introduced.

Preston were to retain the title won in that first season and finished second in the next three campaigns. Yet having proposed the commissioning of the handsome Football League championship trophy, they never actually lifted it.

Rival powers poured into the void. Sunderland, dubbed 'The Team of All the Talents', were champions in only their third season, 1892/93, repeating the feat two years later. Aston Villa won five championships (and three FA Cups, including the double in 1897) before Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 – when Liverpool, nine years after their formation, took their first title. Notts County were the only one of the 12 founder members to finish in the top six.

Another measure of the pace of change that year was Preston’s relegation. One of their directors, Tom Houghton, proposed that the League increase the First Division to 20 clubs, thereby keeping the one-time Invincibles up. He was unsuccessful.

The West Riding of Yorkshire was then a rugby league stronghold. The Football League’s desire to make inroads there was underlined by the election of Bradford City to the Second Division in 1903 before they had so much as played a game.

The first of many for United

Five years later, City were in the First Division and by 1911 their claret and amber ribbons adorned the FA Cup. In the final they beat Newcastle, who themselves went from issuing statements bemoaning the lack of support to carrying off the championship trophy in 1904/05, 1906/07 and 1908/09. In between the second and third of those triumphs came Manchester United's first title. By 1910, United had moved to Old Trafford - and the rest is history.

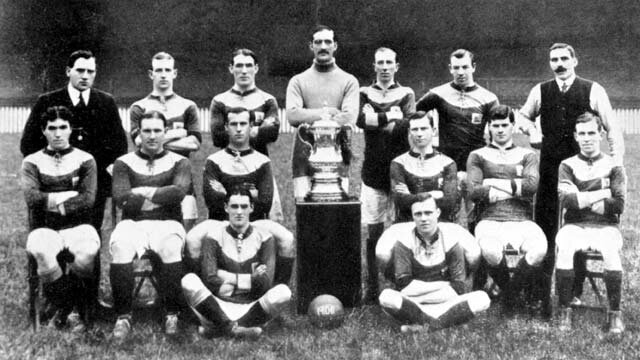

(The 1911 FA Cup winning Bradford City team.)

Newcastle's third title was tarnished by an incredible 9-1 home loss to Sunderland. The Tyne-Wear reserve derby was being contested simultaneously at Roker Park, where the man deputed to post the score from St James’ Park was attacked when it reached 1-7. Locals assumed he was making it up.

While Newcastle were pre-eminent in importing Scots, their captain, Colin Veitch, was a Geordie. The England international was also a playwright, composer and conductor, chairman of the Players' Union, and later a journalist independently minded enough to incur a ban from the St James’ press enclosure.

The final season before the Great War, 1913/14, showed how far The Football League had come. Blackburn were champions, Preston went down again and Chelsea, formed less than a decade earlier, finished eighth.

Curiously, two of the today’s great powerhouses, Manchester City and United, were locked together on points in 13th and 14th place respectively, as were Everton (15th) and Liverpool (16th). In the Second Division, Bradford Park Avenue pipped Woolwich Arsenal and Leeds City to second spot behind Notts County.

Many of the England's finest went off to engage in an altogether more deadly conflict, but the template for the greatest League in the world had been established.

Between the Wars

When the Football League resumed after the Grest War on 30th August 1919, it included an additional four clubs and make up two divisions of 22. The League's expansion continued apace and the crowds followed, relishing the camaraderie and escapism of football.

The following season, the leading clubs from the Southern League were invited to form a third division, which was split regionally the following year into the Third Division South and Third Division North. With one team from each division promoted to the Second Division, the two relegated clubs would be assigned to the more appropriate regional division, though Midlands clubs like Mansfield or Walsall would sometimes be moved from one to the other to maintain equal balance. In 1923, The League's membership increased again to four equal divisions of 22 clubs, which was maintained until after the Second World War.

After 15 years of debate, there was a notable change on the pitch too as the offside law was amended to reduce the number of opponents required between the attacking player and goal from three to two. This led to a significant increase in the number of goals scored, with the 4,700 strikes recorded in the last season of the old rule rocketing to 6,373 in the new law’s debut campaign.

Supporters drank in the added goalmouth action but more goals didn’t always mean higher standards, as defences struggled to adjust and the likes of William ‘Dixie’ Dean forged grand reputations. Dean plundered a League record unlikely to be bettered in 1927/28, when his 60 strikes helped Everton to title glory and pipped George Camsell’s record set only a season earlier in Middlesbrough colours.

(Everton's Dixie Dean on the ball at Goodison Park in 1930.)

The legend of Herbert

In an era of expansion and innovation, it was one man who took up the task of expanding minds. Herbert Chapman, a former Tottenham Hotspur journeyman, had been pushing the boundaries right from his playing days – if not with his footballing skills but by sporting yellow boots more akin to modern times. Talent-spotter, organiser, motivator and businessman, Chapman set about revolutionising the role of manager and though many might suggest Sir Alex Ferguson is the greatest, the mould was first cast by a Yorkshireman at Huddersfield Town.

Chapman joined Town in 1920 and in spite of limited budget, resource and enthusiasm amongst the club’s fanbase, he transformed The Terriers into a title-winning force between 1924 and 1926, before taking the magic touch back to North London – though this time with Arsenal. Another trio of consecutive titles, a feat matched only by Liverpool to this day, confirmed his legendary status.

Invention and modernisation were the foundation of his then unparalleled success, as new formations with a greater emphasis on defending allowed his teams to combat the tricky new offside rule. Ironically it was a striker in Chapman’s ranks, Charlie Buchan, who pushed for a more defensive approach in an era when 2-3-5 was the formation of choice. It was only after a 7-0 thrashing at the hands of Newcastle that Chapman considered the new approach, but there was no doubt who perfected it.

Scoring goals was no less important to the Arsenal manager’s success, illustrated by the record sum paid to Bolton Wanderers for David Jack. At £10,890, his was the first five-figure transfer fee, but they would soon become commonplace as the market rapidly expanded. Chapman would go on to ask Everton to name their price for the irresistible Dixie Dean, but fearing the reaction of their fans the offer was declined. A rare failure.

Chapman was one of the game's first modernisers. As well as introducing new tactics and training methods, he championed innovations such as floodlighting, European club competitions, numbered shirts and white balls, all of which came to fruition after his premature death from pneumonia in 1934.

(The Herbert Chapman statue outside Arsenal's Emirates Stadium)

The Highbury model

Arsenal were involved in another slice of history under Chapman, as their clash with Sheffield United became the first match to be broadcast live on BBC radio on January 22nd, 1927. A simple chart of the pitch was made, with eight areas assigned a number so that listeners could follow where the action was taking place. Henry Wakelam then provided the running commentary during the First Division match, while a colleague called out the numbers alongside him. A year later the Gunners again played their part in another first, as they and Chelsea donned the first numbers on shirts in August, 1928. It would not become compulsory until some eleven years later.

They would not hold the record for most goals by one player in a single game however, despite striker Ted Drake racking up seven strikes in the 1935-36 season. That same season saw two players better that tally, with the surreally named Bunny Bell hitting nine for Tranmere Rovers and Luton Town’s John Payne going one better at the expense of Bristol Rovers. Payne would go on to score 55 goals for The Hatters the following season, a club record to this day. Meanwhile, Tranmere were the victors in the League’s highest scoring game, hammering Oldham Athletic 13-4 in Division 3 North on Boxing Day, 1935.

Such records mattered little in an era of domination for Arsenal, who even after Chapman’s untimely passing continued to swell the trophy cabinet, winning the Division 1 title five times and the FA Cup twice in all. Their dominance provoked widespread dislike among opposing fans and in rival boardrooms, but the Highbury club’s model was duly copied and helped drive the game forward.

The Gunners could not lay sole claim to success in the 1930s, however, with the ‘team of boys’ at West Bromwich Albion winning a unique double unlikely to be repeated as they topped the Second Division and won the FA Cup in 1931. Led by Dixie Dean’s unparalleled scoring prowess, Everton also enjoyed a streak of silverware that took in title victories in the top two divisions and the cup in three successive seasons. Man City and Sunderland also enjoyed league and cup triumphs.

(Everton's Dixie Dean holds up the FA Cup.)

Tale of two wars

The Great Depression defined the 1930s and football provided a welcome escape. By this time the Pools had firmly established itself as part of the Saturday ritual for thousands of fans, having been born in the previous decade.

First handed out at Old Trafford in 1923, the coupons gained a huge customer base, with life-changing winnings available in exchange for a small sum. There were wider benefits too, with the Post Office benefitting from an abundance of payments by postal order and taxation on winnings keeping government onside.

While it was hugely popular with supporters, the footballing authorities had long been unimpressed and in 1936, they launched the infamous Pools War in an effort to shut the operators down. Moral objections and fears that betting would corrupt the game had been simmering for some time, to the extent that two-years prior a Football League committee had refused to sanction an opportunity to begin taking a share of pools company’s profits. Presented by Watson Hartley, the idea was revisited in 1935 when the Liverpool accountant returned with the concept that as owners of the fixture list, The League should charge newspapers, sports publications and pools companies for the right to use them.

Rather than achieve his goal, Hartley only succeeded in giving the committee a means to take on their nemesis. Having received assurances over their legal right to copyright, it was League President Charles Sutcliffe who proposed the advantage be used to eradicate betting on the sport, by initially withholding fixtures until the last possible moment and thereby crippling the ability to produce coupons in advance.

The first weekend this was enforced was Saturday, 29th February but secrecy proved difficult to maintain and newspapers managed to publish full fixture lists. Attendances suffered enormously and with clubs damaged more than the pools providers, the ‘war’ was swiftly brought to an end within a fortnight. It would take more than twenty years for The Football League to be legally granted copyright for the fixture list.

Set against a backdrop of Nazi Germany re-entering the Rhineland, however, it was not long before the debate over gambling on football paled into insignificance. A month into the 1939/40 season, it was time for football to take a back seat.

Football's Heyday

Having been suspended in 1939 at the outbreak of the Second World War, the League returned to action seven seasons later and the nation greeted it like an old friend. The public's appetite for live sport was insatiable and aggregate crowds for the first season back were in excess of 35 million.

Attendances continued to boom and in 1948-49, the all-time high was set at 41,244,295, at a time when the estimated UK population was just 50 million. The record crowd for a league match had come the season before, as 83,260 turned up to watch Manchester United host Arsenal.

Expansion continued to accommodate more clubs and their growing number of fans, with the Third Divisions including 24 clubs by 1950, pushing the total number of team to 92. By 1958 the split Third Divisions were no longer regionalised, but divided into third and fourth tiers and so the modern structure was established.

The Wizard of the Dribble

With many of the interwar stars now retired and the next generation having missed seven years of development, the quality of football on show was no match for the level of interest. There were some players that survived the unwanted interlude, however, and no individual captured supporter affection like Sir Stanley Matthews.

His career spanned four decades, beginning as a 19-year-old in Stoke City colours and ending at the incredible age of 50 with the same club. It was with Blackpool that he most closely identified, however, as the ‘wizard of the dribble’ wowed the watching masses with an exceptional talent for beating defenders that had to be seen to be believed. The only player to have been knighted during his playing career, Matthews set numerous records including the oldest man to play a First Division match and to score a goal. He eventually retired in 1965, a Football League icon and national institution.

Other stars of the era included Arthur Rowley, whose 21-year career saw him amass a record to make even Dixie Dean glower with envy – 433 league goals in 619 appearances. There were new heroes from abroad too, with few better illustrations than 1956 FWA Footballer of the Year Bert Trautmann. The former Luftwaffe paratrooper settled in Lancashire following a spell as a prisoner of war, but his on-field skills softened attitudes and attracted acclaim sufficient for him to become the first non-British player to earn the award.

Tale of Two Managers

If Herbert Chapman was the managerial giant of the 1930s, Matt Busby would pick up the reigns in the post-war years. Like Chapman, there was a hint of irony about his later success with Manchester United given he had spent his career playing for rivals Man City and Liverpool, but Busby made more impact in his time on the pitch.

In 1945, Busby was appointed Manchester United manager and with a crop of promising players, he helped elevate the club to a new level. His impact was immediate and four second-place finishes in five seasons was just the beginning. The title was secured three times in the seasons leading up to the Munich Air Disaster in 1958, in which eight United players were among the 23 people killed. Despite the heart-wrenching setback, Busby rebuilt the team almost from scratch and added two further League titles in the 1960s.

He did have to share the managerial limelight, however, as further south Stan Cullis was making history of his own at Wolverhampton Wanderers. Cullis admitted modelling his style on Busby’s as a player, but once in management the pair had very different ideas. Known for developing so-called ‘kick-and-rush’ football, the former Wolves player (he made over 150 appearances for Wolves) set about making his team a powerhouse of world football. Wider success was built on three top flight titles between 1954 and 1959, not to mention a European clash with Honved of Budapest – a team featuring the mighty Puskas – which they won and duly crowned themselves and The Football League the world’s best.

(Manchester United manager Matt Busby with his players at training.)

Floodlight Football

Long after his passing, Herbert Chapman's vision of floodlit football was finally realised on February 22, 1956, when Portsmouth played Newcastle United in a League match at Fratton Park. The debut was held up by more than 90 minutes courtesy of a fuse failure but once corrected, it proved a big hit with the fans. Coupled with the white ball, which itself had only been introduced in 1951, evening games became synonymous with added excitement and were soon the norm across The League.

These matches meant easing fixture congestion in bad weather, but more importantly opened up new revenue streams. Having been appointed three years earlier, Alan Hardaker made perhaps his most notable contribution as Secretary of The Football League in 1960 by proposing a new knockout competition – The League Cup. Aston Villa were fitting winners of the first final, which was played over two legs, and it was only seven years on that the final became a one-off game at Wembley Stadium.

Television companies were also fond of midweek football under the lights and with ITV competing with the BBC, the income opportunity was plain to see. In spite of fears around damaging attendances, the first League televised match went ahead in 1960, with Blackpool v Bolton Wanderers the fixture to write itself into history.

(Wembley Stadium under the glow of floodlights in 1955.)

The Maximum Wage

First touted in the 1890s as a means to combat player poaching, the maximum wage had come into force from the 1901/02 season and restricted players to receiving no more than £4 per week. While this had risen to £20 by the early 1960s, a campaign began to bring this restrictive practice to an end entirely.

Spearheaded by the Professional Footballers' Association, and in particular by Chairman Jimmy Hill, the case for abolition was taken to the Ministry of Labour. In a new era of commercial growth and televised games, there was more money in the game than ever before, yet players were not only subject to wage caps, but also to the ‘retain and transfer system’ which restricted movement even when their contract came to an end.

Both were now subject of an official dispute and with foreign leagues offering far richer rewards – Leeds United’s John Charles was alleged to have received a £10,000 signing-on fee when he moved to Juventus – and public opinion swayed by the likes of Sir Stanley Matthews, the players had the upper hand. Even so, it took the threat of strike action to bring the matter to a head. Having rejected League proposals to first increase and then abolish the maximum wage alone, the growing threat of a League campaign without its professionals saw The League concede in January 1961. Though the battle against the retain and transfer would rumble on until George Eastham’s High Court victory over his transfer from Newcastle to Arsenal, the maximum wage was abolished with immediate effect.

(George Eastham - pictured on the right - outside the High Court in 1961)

Players were free to negotiate their own terms and Fulham's Johnny Haynes immediately became the first player to receive £100 a week. The move did little to stem the flow of talent to foreign shores; Haynes’ England teammate Jimmy Greaves moved to AC Milan and in the same year, Manchester City became the first English club to be involved in a six-figure transaction when they accepted Torino’s £100,000 offer for Denis Law.

The English game continued to thrive, however, as Bill Nicholson led his 1961 Tottenham Hotspur side to the first League and Cup Double since Aston Villa's at the end of the previous century. Division Four winners Peterborough United were also worthy of attention given their incredible forward line – led by 50-goal Terry Bly – set a new record of 134 league goals. Bly remains the last player to have scored a half century of league strikes in one season.

Boom and Bust

The 1960s ushered in a glorious era for English football, as The Football League’s finest made their mark at home and abroad. Silverware was shared between Sir Matt Busby’s latest incarnation at Manchester United – a team that featured luminaries such as Denis Law, Bobby Charlton and the irrepressible George Best – and Bill Shankly’s famous Liverpool side.

Up on Merseyside, Shankly had taken over at Liverpool when the Reds were struggling in the Second Division but quickly laid the foundations for future success, winning the title in 1964 and 1966. Recognised as one of the great motivators, the confident Scot was also known for his quick wit and many a quote became ingrained in football folklore. “Some people believe football is a matter of life and death,” he famously mused, “I can assure you it is much, much more important than that.”

In 1964, Liverpool’s clash with Arsenal was the first to be featured on the brand new Match of the Day programme on BBC2, a game they won 3-2. They would be picked out for the first colour broadcast in November 1969 too, meeting West Ham United. Coverage was also growing in print media, too, as Football League Review magazine hit the shelves a year later. Across Stanley Park, Everton vied to keep up with the neighbours and paid £100,000 for Blackpool’s Alan Ball – a first between two English clubs – in 1966. It proved a busy year for Ball.

(Alan Ball posing in his Everton shirt in 1969.)

Best of the Best?

Considered by many to be the most talented player of his generation – and arguably of all-time – George Best captured the hearts of both football supporters and adoring female fans. He was the embodiment of the new celebrity footballer, performing wonders on the pitch while living a high-profile glamourous life of it.

Having joined Manchester United as a 16-year-old, Best would debut for the club just a year later and go on to score 137 goals in 361 league games, despite mainly operating as a winger. Sir Matt Busby described him as “the most gifted player I have ever seen” and he collected sufficient honours to support the notion, including two league titles, a European Cup and individual rewards as English and European Player of the Year in 1968.

The contrasts with the likes of previous stars like Sir Stanley Matthews made his playboy lifestyle a point of contention for the purists, but Best was undoubtedly an icon of his era and is still remembered as a genius of the game.

(Manchester United's George Best in 1970)

Red the Colour

After Arsenal became only the fourth club to complete the League and Cup double, clinching the 1971 Championship at Tottenham, the 1970s were dominated by sides managed by Brian Clough and Bob Paisley. Clough radically transformed Derby County and Nottingham Forest, winning three League titles between them, and back-to-back European Cups with Forest. Domestically the side in red went 42-league games without defeat, setting a new Football League record, and broke new ground in the transfer market too when they paid £1,000,000 to prise Trevor Francis from Birmingham in 1979.

Paisley, meanwhile, stepped out of the shadows of Bill Shankly in 1974 and in the next nine years led Liverpool to six League titles, three European Cups, one UEFA Cup and three League Cups before handing over to Joe Fagan and Kenny Dalglish. That wasn’t the end of the success, however, and by the end of the ‘80s Liverpool had won the League 11 times in 18 seasons.

During this time the Anfield outfit had become a hugely marketable commodity and took advantage by becoming the first to put a sponsor on their shirt. Sponsorship was a growing force and The League itself would soon follow suit, making its cup competition the first to bear a sponsor’s name in the title after an agreement with the Milk Marketing Board. The Milk Cup would last four years before a new sponsor, Littlewoods, took over in 1986 – a marked change from the days of the Pools War. In the interim Canon took the title sponsorship of The Football League for the first time, as new revenue streams continued to boost the game’s coffers.

(Liverpool manager Bob Paisley holds the League Championship trophy aloft in 1983.)

Football’s Lowest Ebb

While television audiences and newspaper coverage continued to reflect the nation’s obsession with football, the game was rapidly heading towards crisis point. Decaying stadiums and football hooliganism were taking their toll on attendances and in May 1985, two tragedies within a matter of weeks would take the game to a new low.

Within three weeks of the Heysel disaster, which saw 39 deaths in the Brussels stadium and English clubs subsequently banned from European competition, there was a traumatic blow on home soil at Valley Parade, home of Bradford City. Celebrating lifting the Division Three trophy before their final league game of the season with Lincoln City, the main stand was ravaged by the worst fire disaster in English football history. More than 200 people were injured and 56 lost their lives.

(The fire memorial outside of Bradford City's Valley Parade.)

Time for a Change

Before 1965 teams were forced to play on with a less-than-full complement of injured players were unable to continue; the introduction of one named substitute per team allowed an injured player to be replaced. Keith Peacock of Charlton was the first to come off the bench in August 1965, as he entered the fray in a Division Two match with Bolton Wanderers. The next season it was agreed the allotted substitute could be used at the manager’s discretion, but not until 1987 would the number of replacements be upped to two per team.

Further rule changes arrived in the following decade, as The Football League scrapped the two-up, two-down promotion and relegation system in 1973, and replaced it with three-up, three-down. Three years later, the criteria for separating clubs finishing on the same number of points was changed from goal average (goals scored divided by goals conceded) to goal difference (the difference between goals scored and goals conceded). Sandwiched in between, the first Football League game to be played on a Sunday was a London derby in Division Two between Millwall and Fulham. Played at The Den, the Lions’ season-high 15,143 attendance saw Brian Clark score the first ever Sunday strike.

In 1981, it was decided to award three points for a win, rather than two, in a further effort to encourage attacking football. The idea was the brainchild of Coventry City Chairman and BBC Broadcaster Jimmy Hill and would go on to be used throughout the world. With the new rule in force, York City became the first team to breach the 100-point mark as they won Division Four in 1982/83. In 32-years since the rule change, only nine further clubs have achieved the distinction. Later that year, The Football League Trophy was launched under the title ‘Associate Members Cup,’ reflecting the fact Division Three and Four clubs were not classed as full members at the time.

A New Promotion

Automatic promotion and relegation was brought in between the Fourth Division and the Football Conference in 1986/87, while simultaneously another defining innovation was approved – the Play-Offs. First mooted by League Secretary Alan Hardaker in the 1970s, the idea was picked up by Brentford Chairman Martin Lange and it was he who would go on to be labelled their creator-in-chief.

Lange had initially suggested the Play-Offs be introduced into the Third and Fourth Divisions as part of the Heathrow Agreement, which was focused on reducing the number of sides in the top flight. Such was the excitement around the idea, however, that the Second Division would adopt them too as clubs recognised the opportunity to extend the excitement of a season for fans of clubs outside the automatic promotion places. This in turn helped ease tensions between the top two tiers in the short-term, while having an undeniable impact on attendances and end-of-season drama right up until the modern day with crowds having more than doubled since their introduction.

A New Dawn

Football had reached crisis point during the 1980s and the Hillsborough disaster, in which 96 Liverpool supporters lost their lives was its nadir. Enough was deemed enough and the Taylor Report which followed would help lead football into better times. The changes made to stadia would transform the matchday environment and allow the authorities to turn the tide in the battle with the hooligan element.

The cost of transforming football’s architecture was estimated at £300 million but Taylor insisted: “The years of patching up grounds, of having periodic disasters and narrowly avoiding others by muddling through on a wing and a prayer must be over.”

Breaking Away

The events at Hillsborough overshadowed the game as the ‘80s drew to a close but on the pitch, there was still plenty to adore about the game. Neutrals gasped and Arsenal celebrated in jubilant fashion as Michael Thomas burst through the Liverpool defence in the 1988/89 title decider at Anfield and scored the decisive goal that took the title to North London. Growth continued in the transfer market too, with £2million fees paid for both Tony Cottee and Paul Gascoigne in England.

There had been keen competition throughout the 1980s between terrestrial broadcasters for the rights to screen live League matches. However, the arrival of satellite television changed the landscape forever. It coincided with the FA unveiling their ‘Blueprint for Football’ document, which put forward the idea of a Super League of 18 clubs, a proposal the top clubs had been discussing for several years in an attempt to keep more of The League's revenue and voting rights for themselves.

The Football League resisted the proposals strongly producing its alternative plans in the ‘One Game One Team One Voice document’. However, on 14 June 1991, 16 First Division clubs signed a document of intent to join the newly formed Premier League, and eventually all 22 top flight clubs tendered their resignations from The League. By September, the breakaway league had become official.

The Premier League struck a five-year television deal with Sky Sports and the BBC, worth £304 million, while The Football League sealed a £24 million deal with ITV for live coverage of its games.

Onwards and Upwards

The three-division Football League regrouped with 70 clubs in the first three seasons after the split, before expanding to the present-day 72 club set-up when the Premier League reduced to 20 clubs. The divisions were renamed Divisions One, Two and Three to reflect the changes.

Suggestions that the split would be the death knell of many professional football clubs proved unfounded as football at all levels boomed in the new satellite television era. The Football League flourished in the face of adversity and in 2001 signed a three-year, £315 million broadcasting deal with ITV Digital, the biggest in its history. However, by March 2002 the channel was in administration leading to serious repercussions for member clubs. More than 30 would go into administration in the immediate aftermath.

The appointment as Chairman of Sir Brian Mawhinney (now Lord Mawhinney), the former Chairman of the Conservative Party, in January 2003, proved to be the catalyst for a drive towards good governance and a raft of measures that would improve the financial position of clubs in the post ITV Digital era. Over the next 18 months The Football League pioneered a host of measures, including publishing club payments to agents, a 'sporting sanction' of 10 points for clubs entering administration, a 'fit and proper persons' test for club directors and majority shareholders and the introduction of an independent non-executive director on The Football League Board.

The League also underwent a substantial re-branding, under which it sought to reclaim its heritage by renaming the divisions ‘The Championship’, ‘League 1’ and ‘League 2’. As part of the initiative, The League developed a series of community initiatives, including encouraging young supporters to attend matches at minimal cost under the 'Fans of the Future' campaign.

"Over the last few years the League's standing has been enhanced, both commercially and competitively, as we have delivered real football for real fans," Lord Mawhinney said in 2007. William McGregor would doubtless have approved.

2009-2013 - A New Era

In November 2009 Lord Mawhinney announced he was standing down as Chairman of The Football League after seven years at the helm. Greg Clarke, the former Chief Executive of Cable and Wireless Communications Plc, was named as his replacement.

In 2012/13 after two years of detailed discussions, The Football League and its clubs agreed a Financial Fair Play framework to operate in all three divisions. In the Championship, clubs have introduced a breakeven approach based on the UEFA Financial Fair Play Regulations. It will require clubs to stay within pre-defined limits on losses and shareholder equity investment that will reduce significantly over a five season timeframe.

In League 1 and League 2, clubs have implemented the Salary Cost Management Protocol (SCMP) that has been in use in the latter division since 2004/05. The SCMP broadly limits spending on total player wages to a proportion of each club’s turnover.

The Football League today represents the largest single body of fully professional clubs in world football. Its clubs employ more than 20,000 full and part-time staff and have more than 10,000 professional, apprentice and schoolboy footballers on their books.

Attendances in the modern era are at their highest levels for 50 years with the 17.1m fans that watched matches during the 2009/10 season representing a significant increase on the 10.9m that watched matches in 1992/93, the first season after the split with the Premier League.

The Championship alone has become the fourth most watched league in Europe with only Germany's Bundesliga, the Premier League and Spain's La Liga boasting more fans through the turnstiles, with The Football League's top division attracting even more supporters than Italy's Serie A and France's Ligue 1. Crowds in Leagues 1 and 2 also comfortably outstrip those recorded at comparable levels of football in all Europe's other major footballing nations.